Status of Ahtna Dene Language

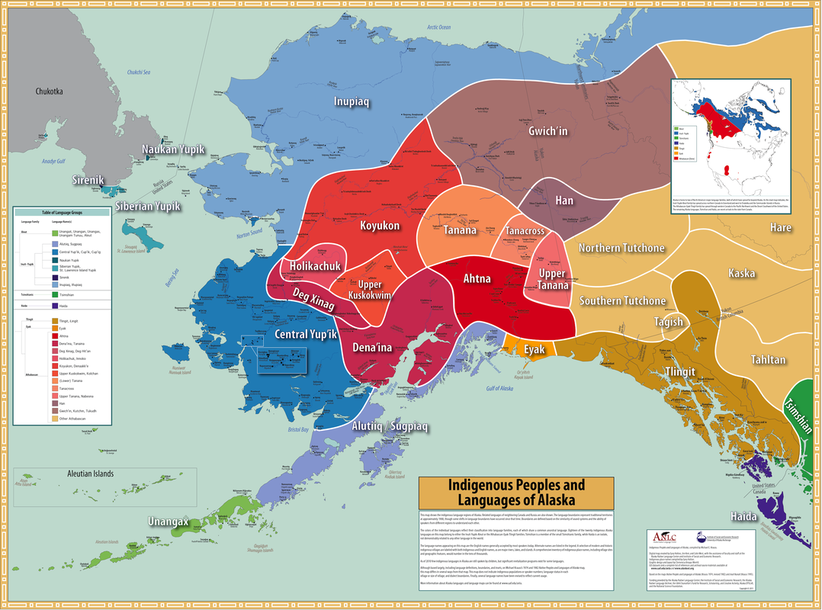

Map: Copyright © 2011, Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage

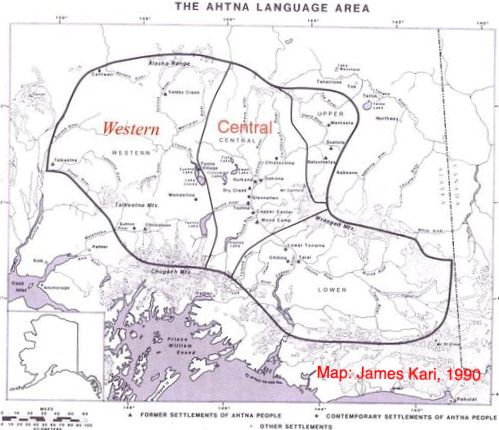

Ahtna Athabaskan is one of the 11 Athabaskan languages in Alaska. It is spoken in the south-central region of the state. There are four regional dialects for Ahtna; they are called Lower, Upper, Central, and Western. There are many villages located in the Ahtna dialect system region, (see Figure 1); the Lower Dialect include the villages of Chitina, Lower Tonsina, Chistochina, and some of the Copper Center area, the Upper Dialect region is where Mentasta village is located. Central Dialect villages are located at Tazlina, Gulkana, Gakona, and Copper Center. The Western Dialect villages are Cantwell, Mendeltna, Sutton, Tyone Village, Chickaloon, Valdez Creek, and some people in Talkeetna also speak this dialect.

For this class we will focus on the Western and Central regions. Our village of Chickaloon is located in the Western region, although the last fluent speaker, Katherine Wade, of the area passed in 2009. Chickaloon Village had to meet the challenge of fluency with finding another proficient Ahtna speaker to continue the work. Jeanie Maxim of Gulkana and Markle Pete of Tazlina Villages, who are both Central Dialect Speakers, agreed to assist with the Chickaloon language learning. These Elders have provided many hours of language and insightful ways of connecting language to the deeper meaning of language.

Kari (1990) reports fewer than 100 fluent speakers of Ahtna, who are all over the age of forty (p. vii). Currently, the Ahtna Language has even fewer fluent speakers, and all fluent speakers are over the age of 70 and approximately less than 25 live in the upper regions of the Ahtna area (Krauss, 2007).

By some estimates all eleven Athabaskan languages now spoken in Alaska are moribund, that is, they are no longer being actively acquired by children (Krauss 1998). Without radical efforts to reverse this trend, maintenance of Alaska Athabaskan languages seems extremely unlikely. However, the conventional view of language maintenance which underlies this conclusion assumes a static view of language. While Alaska Athabaskan languages may be unlikely to be maintained in the same form and with the same range of uses, it may nonetheless be possible for these languages to be relearned in new forms for new purposes (Holton, 2009).

Our village has begun to adapt our language learning by merging Ahtna language with fluent speakers from the upper Ahtna regions. Although there are concerns over using a different dialect for our area, my village has embraced this process. There have been other challenges because ideally, the Ahtna language needs to be taught or learned in the home, where real language learning begins. Language acquisition from birth results in native speakers of a language through intergenerational transmission; this is where the development of sounds and meaning of sounds are learned for native speakers (Lightbown & Spada, 2007). As previously stated, many fluent Ahtna speakers are over the age of 70 and are not able to travel. Thus, language learners living in other villages must travel great distances and are not able to spend meaningful time that is needed to learn. Once our Elders are gone, so is the language that goes with them. Baker (2011) states “A language dies with the last speaker of that language” (p. 41). It is vital to utilize the Funds of Knowledge, the living resources of our communities, and reinstate Native language communication with our children to perpetuate new language for future generation.

The endangered nature of these indigenous languages give rise to many academic challenges. When a language has few speakers, learners must rely on other, often highly technical resources, such as dictionaries and recordings. Accessing these resources can require, learning linguistics, essentially having to learning another language to learn their target language. Literacy has been vital to learning and teaching Dena’ina and Ahtna Dene. Dictionaries, language systems and learning materials have been developed, but many language learners (who just want to speak the language) resist or not interested in learning these language systems of reading and writing.

Lack of literacy can be overcome by understanding how a person best learns and then encouraging that learning process. Creating new ways can be developed to construct linguistic terms to language concepts that are familiar to language learners.

Crucial to this is using relevant cultural thinking processes to convey these language concepts, such as Funds of Knowledge practices, in teaching, so that language learners have a familiar knowledge base as they approach the learning.

Getting students out of the classroom and have them experience cultural activities and real life approaches to learning promotes is where learners can utilize skills to learn. Concepts of cultural practices that are observed by the learner and participants, such practices could be cutting fish, cooking soup, hunting moose, picking berries, harvesting birch bark, sewing or beading can be highly entrenched in the learning of words. Cope and Kalantzis (2009) revealed that our everyday lives could be explained through using multimodalities (many different ways to learning activity, hear-taste-touch-smell-experence). They state that we use many modalities throughout our day to learn and make meaning (p. 13). Multimodalies can also support language learning in the classroom. Teachers and Language Learners can learn words and meanings by using the dictionaries and recording before the activity and the language transmitted through Master Language Speakers. They also ask questions and model for students how to answer in the language.

Another aspect that needs to be considered for language development and continuation is having Elders as teachers and as participants in the classroom. Having experts in the language bring Funds of Knowledge (FoK) that enriched the process. Funds of Knowledge are defined by González, et al., (2005) knowledge from the community that is brought into the classroom. As language learners rely on written resources developing new material must be ensure that the material is not taken out of context. First language speakers grew up in the language and know language differently, not through literacy, so a written interpretation may not the be the same as Native ways of knowing. González, et al., (2005) describe FoK as bringing the outside of the classroom to the classroom, which adds a rich, authentic, and comfortable atmosphere that may be familiar to students (p. 74). Having Elders in the classroom as part of the positive teaching allows students to learn to care for the Elders and for one another. Getting tea for the Elders, which is a sign of respect, or making sure they are comfortable are all values that can be demonstrated and can be acted upon instead of only talked about through the language.

For this class we will focus on the Western and Central regions. Our village of Chickaloon is located in the Western region, although the last fluent speaker, Katherine Wade, of the area passed in 2009. Chickaloon Village had to meet the challenge of fluency with finding another proficient Ahtna speaker to continue the work. Jeanie Maxim of Gulkana and Markle Pete of Tazlina Villages, who are both Central Dialect Speakers, agreed to assist with the Chickaloon language learning. These Elders have provided many hours of language and insightful ways of connecting language to the deeper meaning of language.

Kari (1990) reports fewer than 100 fluent speakers of Ahtna, who are all over the age of forty (p. vii). Currently, the Ahtna Language has even fewer fluent speakers, and all fluent speakers are over the age of 70 and approximately less than 25 live in the upper regions of the Ahtna area (Krauss, 2007).

By some estimates all eleven Athabaskan languages now spoken in Alaska are moribund, that is, they are no longer being actively acquired by children (Krauss 1998). Without radical efforts to reverse this trend, maintenance of Alaska Athabaskan languages seems extremely unlikely. However, the conventional view of language maintenance which underlies this conclusion assumes a static view of language. While Alaska Athabaskan languages may be unlikely to be maintained in the same form and with the same range of uses, it may nonetheless be possible for these languages to be relearned in new forms for new purposes (Holton, 2009).

Our village has begun to adapt our language learning by merging Ahtna language with fluent speakers from the upper Ahtna regions. Although there are concerns over using a different dialect for our area, my village has embraced this process. There have been other challenges because ideally, the Ahtna language needs to be taught or learned in the home, where real language learning begins. Language acquisition from birth results in native speakers of a language through intergenerational transmission; this is where the development of sounds and meaning of sounds are learned for native speakers (Lightbown & Spada, 2007). As previously stated, many fluent Ahtna speakers are over the age of 70 and are not able to travel. Thus, language learners living in other villages must travel great distances and are not able to spend meaningful time that is needed to learn. Once our Elders are gone, so is the language that goes with them. Baker (2011) states “A language dies with the last speaker of that language” (p. 41). It is vital to utilize the Funds of Knowledge, the living resources of our communities, and reinstate Native language communication with our children to perpetuate new language for future generation.

The endangered nature of these indigenous languages give rise to many academic challenges. When a language has few speakers, learners must rely on other, often highly technical resources, such as dictionaries and recordings. Accessing these resources can require, learning linguistics, essentially having to learning another language to learn their target language. Literacy has been vital to learning and teaching Dena’ina and Ahtna Dene. Dictionaries, language systems and learning materials have been developed, but many language learners (who just want to speak the language) resist or not interested in learning these language systems of reading and writing.

Lack of literacy can be overcome by understanding how a person best learns and then encouraging that learning process. Creating new ways can be developed to construct linguistic terms to language concepts that are familiar to language learners.

Crucial to this is using relevant cultural thinking processes to convey these language concepts, such as Funds of Knowledge practices, in teaching, so that language learners have a familiar knowledge base as they approach the learning.

Getting students out of the classroom and have them experience cultural activities and real life approaches to learning promotes is where learners can utilize skills to learn. Concepts of cultural practices that are observed by the learner and participants, such practices could be cutting fish, cooking soup, hunting moose, picking berries, harvesting birch bark, sewing or beading can be highly entrenched in the learning of words. Cope and Kalantzis (2009) revealed that our everyday lives could be explained through using multimodalities (many different ways to learning activity, hear-taste-touch-smell-experence). They state that we use many modalities throughout our day to learn and make meaning (p. 13). Multimodalies can also support language learning in the classroom. Teachers and Language Learners can learn words and meanings by using the dictionaries and recording before the activity and the language transmitted through Master Language Speakers. They also ask questions and model for students how to answer in the language.

Another aspect that needs to be considered for language development and continuation is having Elders as teachers and as participants in the classroom. Having experts in the language bring Funds of Knowledge (FoK) that enriched the process. Funds of Knowledge are defined by González, et al., (2005) knowledge from the community that is brought into the classroom. As language learners rely on written resources developing new material must be ensure that the material is not taken out of context. First language speakers grew up in the language and know language differently, not through literacy, so a written interpretation may not the be the same as Native ways of knowing. González, et al., (2005) describe FoK as bringing the outside of the classroom to the classroom, which adds a rich, authentic, and comfortable atmosphere that may be familiar to students (p. 74). Having Elders in the classroom as part of the positive teaching allows students to learn to care for the Elders and for one another. Getting tea for the Elders, which is a sign of respect, or making sure they are comfortable are all values that can be demonstrated and can be acted upon instead of only talked about through the language.

|

When I was learning to tanning a moose hide I tried many different ways to tan, along with having to work my day job, family obligations and other life responsibilities. I went through many ups and down and many doubts of completing this process. There was a huge amount of strength and stamina that was needed to finish the skin and a fair amount of studying of what others had done. In the end, the best method was how the Elders had instructed me. Their process was flawless by using the natural tools combined with the elements of weather. I also had many friends and family helping me, encouraging me to keep going, not to give up and supporting me with their time and strength to finish.

|

I compare this experience to my learning of Native language. There are many different methods to learn language that are out there, but learning what best fits my life style with how my Elders want me to learn is vital to my learning language. I have to study and prep before hand and have all my tools ready. I have many ups and downs along with doubts, but with my community has been there to support and push me forward, I would not have been able to finish.

Language learning can be work, but it can be key that unlocks self identity and links us to our past. As language learners we must relearn to take back our language and not wait to have it given to us.

Language learning can be work, but it can be key that unlocks self identity and links us to our past. As language learners we must relearn to take back our language and not wait to have it given to us.